The story of Megan’s and my shared ancestors can be found in our article Shared Ancestors and Shared Experiences. Whilst this is fascinating, it does not show all the complexity of our family linkages. Mere descriptions cannot adequately portray the extent of the complexity which was impressed on me when I tried to construct the family trees that I used in the article. I was forced to keep only the simple and direct lines of connection and present only those people who I discussed. But I still needed multiple descendant charts just for the main family connections.

I wanted to put everything together so that the true complexity and extent of the interconnectedness could be seen at a glance, but the family tree applications are not up to the task, and the online services are even less useful. There are just too many cross linkages in our families: cousin marriages; multiple children of a marriage separately linking to us; these children linking at different generational levels; people marrying multiple times with children from each family linking to us; these linkages being at different generational levels.

I turned to a package that is used for genetic mapping and analysis. This suffers a little from the opposite problem to the family tree packages in that it is designed for analysing massively complex networks and doesn’t have the most elegant charting interface. Nonetheless, it was able to arrange the families and generations into optimised layouts with the least overlapping which I could then adjust to get more readable images.

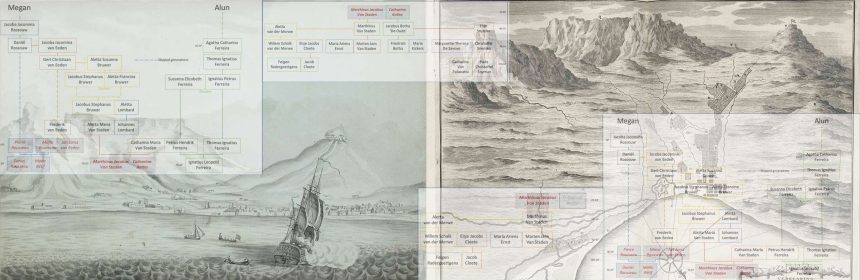

I have constructed two layouts. The first replicates, as far as possible, the standard hierarchical network that is usually used to show ancestral lineages. Megan and I are at the top with earlier generations in layers below us getting wider and wider as we go down thirteen generations. The second shows us at the centre (more or less) of a spider web of ancestors clustered in families with the earlier generations further and further from us. The first is better for visualising the generational linkages. The second is better for visualising the familial linkages.

Both trees are too complicated to lay out for a web page so they are presented in PDF files. If you click on the links below, they will open in a browser window and allow you to see the overall structure. Most browsers, however, will not allow you to zoom in far enough to see all the detail. For this you will need to download the file to your computer and then use Adobe Acrobat Reader (PC or Mac) or Preview (Mac). You can do this by saving the image open in your browser. Every browser does this differently so I leave it to you to figure it out. You can also right click on the links below and select the Save/Download option.

The hierarchical family tree

can be found

HERE (PDF)

Right click to download |

The clustered family tree

can be found

HERE (PDF)

Right click to download |

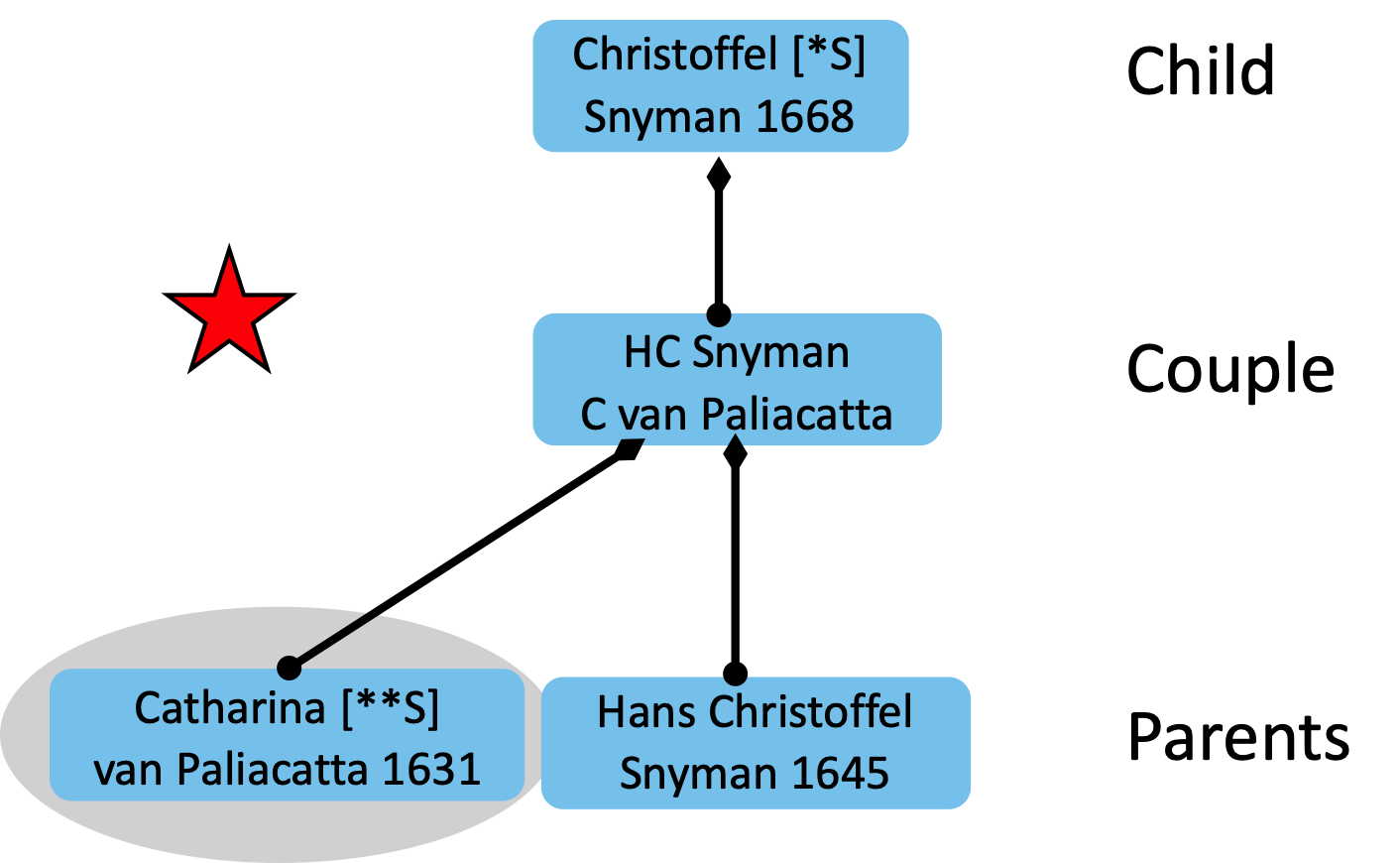

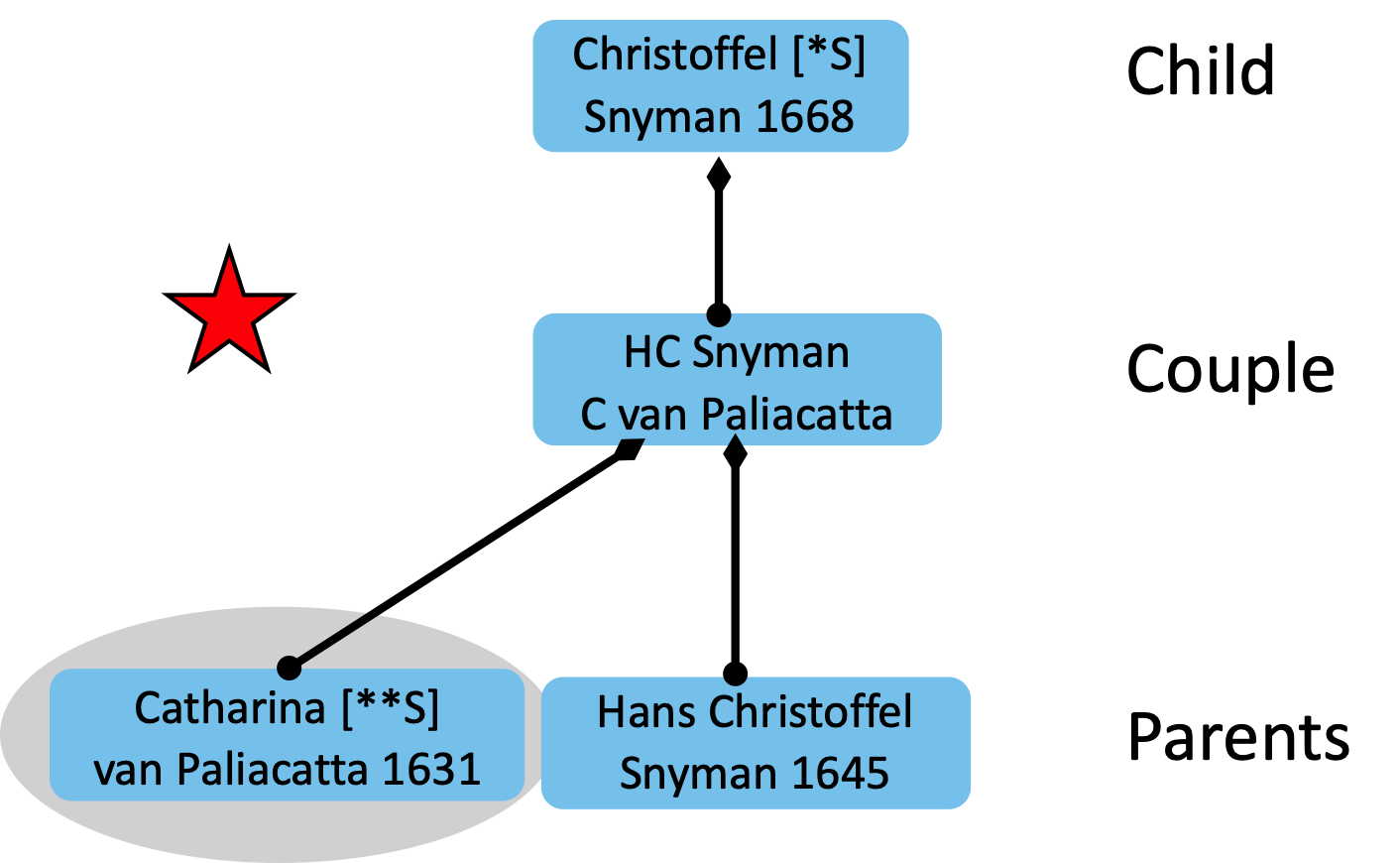

The information is presented in successive layers of Parents/Couple/Children using boxes and arrows as below.

|

Dates are birth years.

Red stars highlight interesting ancestors who appear in the discussion.

The grey ellipses highlight individuals who were either slaves, people of colour, or illegitimate. The detail is in the square brackets:

* – a parent of colour

S – a Slave

I – Illegitimate.

|

Megan’s and my mothers are just shown as “wife” because their maiden names are used as security questions. (The times we live in?!)

Hierarchical layout

The layout is pyramidal rather than the usual square layout because it goes down to thirteen generations before us. The lower levels would be far too wide with a square layout. The structure is quite well ordered down to Level 8 below us when connections start crossing generations and linking the right (Megan’s ancestors) to the left (my ancestors). Levels 9 and 10 are then a spider-web of cross hatchings which thin out in Level 11, mainly due to us not being able to trace all the ancestors back to this level.

The complexity of the interlinkages can be seen by considering the Snyman family that is used in the example above. If you open the hierarchical family tree, you will find them at the bottom in the middle. Their story is here. Christoffel Snyman was born illegitimately as a slave to Catharina van Paliacatta. He was freed when his mother was freed and he was legitimised when his mother then married. He, in turn, married the aristocratic Marguerite de Savoye and they are shown at Level 12 with connection lines radiating upwards cutting across the ordered structure.

Their daughter, Elsje Snyman (born 1697) connects to both Megan and me. She married Jacobus Botha (born 1692) and their daughter, Catharina Botha (born 1714), married Marthinus Jacobus van Staden (born 1706). The Van Staden’s linkage to both of us is discussed here. Their daughter, Catharina Maria (born 1739) links to me via the Ferreira’s making Elsje Snyman my 8th great-grandmother by this route.

Their older daughter, Aletta Maria (born 1731), links to Megan via her marriage to Johannes Lombard (born 1725). He was the son of Elsje Snyman’s younger sister, Johanna Snyman (born 1699), who had married Anthonie Lombard (born 1693). One sister’s son married the other sister’s granddaughter. Aletta Maria and Johannes Lombard link to the Bruwers, the Van Eedens, and Megan’s Ouma via their daughter Aletta Lombard (born 1752). Johanna Snyman is Megan’s 7th great-grandmother by this route, and her sister, Elsje Snyman, is Megan’s 8th great-grandmother.

Their youngest sister, Elizabeth Snyman (born 1706), interestingly, is Megan’s 5th great-grandmother via her marriage to Jan Hendrik van Helsdingen (born 1696) and the marriage of their daughter, Anna Susanna (born 1740), to Christman Joël Ackermann (born 1728) and then on to Megan’s Oupa.

As a result of this, Christoffel and Marguerite Snyman are independently Megan’s 6th, 8th, and 9th great-grandparents, and my 9th great-grandparents! Lots of cross links just from one couple.

Clustered layout

This layout does not attempt to keep track of the generations. It is designed to show the linkages within and between families. Linkages that span the breadth of the hierarchical chart, like Elizabeth Snyman, are frequently close to each other in this chart format.

The software has arranged the family groups around the end point – Megan and me – with the minimum of cross linkages across the chart. We can be found towards the bottom left with a red circle to highlight us.

The high level view shows that the connections within the family groups are fairly well ordered as are those between families that are closely associated like the Rossouws and Van Eedens, and the Mullers and Ferreiras. My ancestors are mainly down in the bottom right while Megan’s, much more extensive group, fills the top half of the diagram.

The more complex interlinkages criss cross across the centre of the diagram. For instance, the Potgieters near the middle who link to the families on both the left and the right. The Bothas and Van Stadens are also key linkage points and do the same.

©Alun Stevens 2020