Richard Walford Stevens at Isandlwana

Richard Walford Stevens at the 60th anniversary of the battle and as a Natal Mounted Police Trooper against the backdrop of the battlefield as seen from the camp.

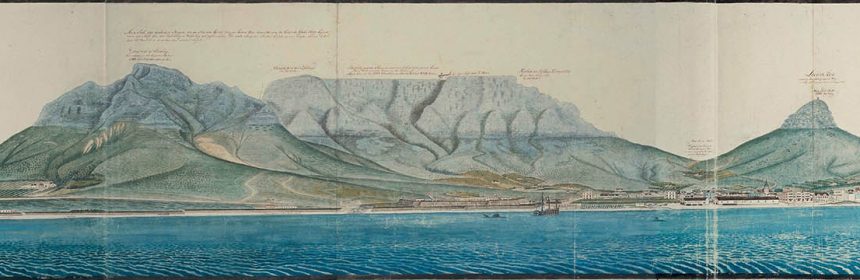

My great grandfather, Richard Walford Stevens, was a 20 year old Trumpeter with the Natal Mounted Police when the Anglo Zulu War began on 11 January 1879. He crossed the Mzinyathi (Buffalo) River into Zululand that day at Rorke’s Drift and was part of the first battle of the war the following day. On 20 January, he had to walk the 11 km to the base of the strange, sphinx-like hill, Isandlwana, because his horse was sick. His sick horse also prevented him from heading out with most of his comrades in a big scouting party the next day so he was in the camp on 22 January 1879 when it was attacked by the main Zulu army of some 20,000 warriors pouring over the ridge and racing towards them.

He played a small part in the spirited forward defence by the mounted troops in “Durnford’s Donga” until they were overwhelmed and had to retreat back to the camp. All was lost by that stage because Zulu warriors were already there when they arrived – stabbing and slashing. His only weapon, a revolver, was broken so he made his harrowing escape down the back of Isandlwana to the Mzinyathi river along the route that became known as the Fugitives’ Trail, now marked by a string of burial cairns. He managed to get across the river into Natal and rode to Helmekaar as one of only nine Natal Mounted Policemen to escape.

He wrote about his experiences to his family back in Witham, Essex, and they sent his letters to the newspapers so we know what he said. Quite a lot it turns out despite the brevity of his letters. And pithy. Which is why he has been much quoted by historians especially regarding the mayhem in the camp.

He had gone to Natal on an adventure and left the police to do the same by going to the diamond fields of Jagersfontein. He did not make his fortune and instead embarked on a career that can best be described as entrepreneurial and opportunistic, but not particularly successful. He had his ups and he had his downs with two bankruptcies and a prosecution for embezzlement. He pleaded guilty but was pardoned by the judge without a conviction being recorded. Amazingly.

He lived out his life with his son and daughter-in-law on their farms in the Witsieshoek and Kestell areas of the Free State.

He valued the comradeship of his first great adventure and was a regular attendee at Isandlwana and Natal Mounted Police reunions. He was remembered as the last survivor of the nine Mounted Policemen who escaped Isandlwana.

His story has taken a lot of work to put together because there were no family records and only sketchy recollections of his life. When I started out, all I had was what my father had told me: his name was Richard William Stevens; he was from England and had fought at Isandlwana; he had married Kate Norton (who was Jewish and possibly called Nortonovski) from Barkly East; he lived with my father’s family on their farm for many years; he liked his reunions and died aged 85 on the way to a reunion; he was never without his fob watch on its chain; he swore by a good suit; and there were his medals. But only some of this was true. Kate Norton, for instance, was baptised and confirmed in the Dutch Reformed Church!

His only remaining mementos are his medals and a fob watch chain that was his pride and joy. It is an interesting story of a young man from a privileged English background who embarked on a colonial adventure. And if he hadn’t managed to avoid the warriors that fateful day in January 1879, it would have been a very short adventure, and I wouldn’t be here to tell what happened to him.

The full story with transcripts of his letters, a detailed explanation to what he said, plus details of his earlier and later life and marriage, can be found .

©Alun Stevens 2023