A dinner party was held in the Glengallan homestead on 16 September 2017 to celebrate the homestead’s 150th anniversary. Megan was invited to speak on behalf of the Marshall descendants and present an overview of the family. This is a transcript of her speech.

Thank you for asking me to speak about my great-great-grandparents, Charles and Charlotte Marshall. It is good to be here, near where the “old house” stood, where my great-grandmother was born in 1859.

Thank you for asking me to speak about my great-great-grandparents, Charles and Charlotte Marshall. It is good to be here, near where the “old house” stood, where my great-grandmother was born in 1859.

Charles and Charlotte were children of the expansion of the British Empire, with close ties to Totnes in Devon.

Charles was born in 1818 at Mauritius, where his father, William, was joint chief of police. William was born in Devon in 1780, and had gone to sea, aged 14, with the East India Company. When he married Louisa Bentall at Totnes in 1810, he joined the Army, and was posted to the Cape of Good Hope, and then Mauritius.

After a failed venture, William returned to England, alone, in 1822, but the family’s fortunes worsened the following March, when Louisa died at Mauritius, aged 39, probably during the cholera pandemic. The children re-joined their father in Scotland a year later.

Four years later, William died suddenly, and the Devon families rallied to care for the orphans. His probate poignantly recorded the children’s election of their uncle, John Bentall, as guardian of their inheritance, which secured their futures.

Four years later, William died suddenly, and the Devon families rallied to care for the orphans. His probate poignantly recorded the children’s election of their uncle, John Bentall, as guardian of their inheritance, which secured their futures.

Charles was a mariner at Totnes by 1841, though details are scant. The only mention I have is of Charles working as third mate on board the Princess Charlotte in 1839.

He became bookkeeper for the Van Diemen’s Land (VDL) Company at Stanley in 1843, a position obtained through his father’s cousin, Edward Marshall of the War Office, a director of that Company. The Tenantry Return for that year uniquely described Charles as “a relation of … Edward Marshall” and as having “capital”.

The VDL Company archive in Hobart is vast. Documents show that in 1846 Charles was appointed Superintendent of Woolnorth at Cape Grim, running the sheep station. He resigned in 1849, with sufficient funds to try his luck in Queensland. By 1851 he was on Glengallan, becoming sole proprietor in July 1852.

Charlotte was born at Albany, Western Australia, in 1838. Her father, William Henry Drake, like his father, lived the peripatetic life of a Commissary. Henry was born in Portugal, where his father served during the Peninsular War. In 1831, Henry was sent to Perth, and there married Louisa Purkis.

He was transferred to Hobart in 1848, and two years later, to Canada, after which he was sent to London. On his arrival there in 1854, he was diverted to the Crimea for the duration of the war. He was stationed at Balaklava, where his wife and eldest daughter joined him. Charlotte and her sister, Laura, stayed with their grandparents in London, attending school.

When hostilities ceased in 1856, the Drakes were re-united in London. Henry’s second cousins, William and Mary Marshall, also from Totnes, were neighbours. Mary (born Benthall) was Charles Marshall’s first cousin, and William, a distant cousin of his.

So, fate ensured that Charles and Charlotte would meet when Charles visited England after going into partnership with John Deuchar. Henry’s Journal tells the story. In August 1856, Edward Marshall of the War Office called. Numerous visits with William and Mary Marshall followed, and, significantly, on the 6th of April 1857, the Drakes dined with them. Henry noted that “Mr. C. Marshall” was present. In May, Charles dined with the Drakes a few times, and had tea with them. In August, Henry, Louisa, Charlotte, and Charles went to an Art Exhibition, and visited the Tower of London.

On the 18th of August, Charlotte’s older sister, Louisa Maria, congratulated her on her engagement, saying, “You know I always said it would give me more pleasure to see you married than anything else … and … I do rejoice to think you will have a husband I like so much & everybody else thinks so highly of.”

Invitations for the Wedding Breakfast went out on the 11th of September, and on the 23rd, Charles and Charlotte were married at St Pancras Parish Chapel, in Camden, by Charles’s second cousin, the Rev. Stephen Hawtrey. Charlotte wore a hand-embroidered Honiton lace veil – the same one my mother wore when she married my father. Henry wrote that “A Party of 37 lunched with us … & at 3 p.m. the Bride & Bridegroom left for Rugby & a tour.”

Charlotte noted in her Journal that they “Left 21 Regents Park Terrace in style, having had an old white satin shoe thrown at us.” The couple explored the Lake District, Edinburgh, and York, and returned to London at the end of October. Henry wrote on the 12th of December that “Charles & Charlotte left Southampton … for Alexandria en route for Australia.” They arrived at Sydney on the 17th of February 1858.

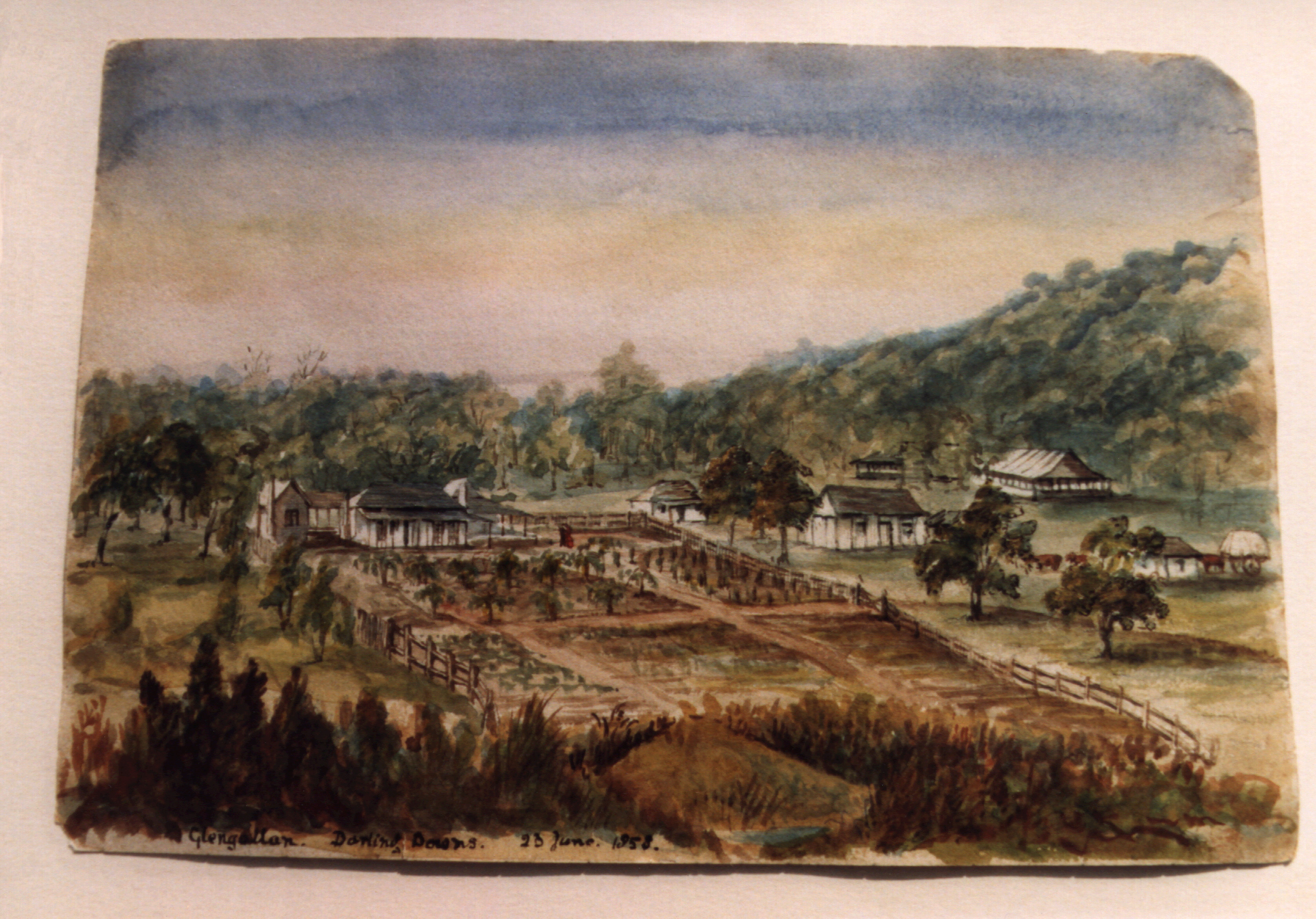

And, so, on the 23rd of February 1859 my great-grandmother, Charlotte Louisa Marshall, was born, here, not long after her mother painted the beautiful watercolour featuring their wooden house, with Mount Marshall in the background. Thirty years later Charlotte told Slade that she was glad she “was not there to see the old house pulled down”.

The Marshalls had six children. Charles Henry, the youngest, was born in 1874, four months after his father’s sudden death. Officially, Charles senior died of “cardiac disease”, but I suspect he died from melanoma. Sir James Paget, London’s leading surgeon, performed what Charles called “a most severe operation” on a “malignant” tumour on his ear in mid-1873. Paget performed another operation in March 1874, when the tumour spread.

My mother told me that Charlotte discovered that Charles had had another family after he died. This family was not mentioned in his will, but we know there was a lost “side letter”, in which it seems he left a bequest. Charlotte wrote to Slade, cryptically saying that following her “dear husband’s death” she had had “very many other very heavy expenses to meet that no one knows of or suspects”.

I have searched high and low for this family, but only recently found the VDL Company Tenantry Report for August 1849, which showed Charles had an unnamed “wife” and “child”. It clearly wasn’t a formalised relationship. Charles did not abandon his secret family, as otherwise I would not have heard about them.

After Charles died, Charlotte had to take care of her investment. Her typically feminine Victorian education had not prepared her for this, but she worked hard to understand and to contribute intelligently.

She remarried in 1883, to the accomplished William Knighton. They signed a pre-marital deed, described by Charlotte to Slade as follows: “I have had a special clause put in … that the management of Glengallan should be carried on by you & by me as heretofore, no one else in England knows as much about it as I do, & I still feel quite capable of doing my part & you will find all just as before.” This prevented Knighton from interfering, though he did help when she was ill, or when family crises intervened. I know Slade didn’t find the Knightons easy to deal with, and vice versa, but relations were always respectful.

Knighton died in 1900, and in 1905 Marshall & Slade was dissolved, after the Government’s repurchase of Glengallan for closer settlement. Charlotte died of old age in 1922 at her home, Caberfeigh, in Redhill, Surrey. She was a remarkable woman: she was raised to be a traditional Victorian wife and mother, but became a successful Victorian capitalist.

The Marshalls’ substantial investment in Glengallan wouldn’t have been as lucrative as it was without the exceptional skill, hard work, and intelligence of both Deuchar and Slade. As the Brisbane Courier noted in November 1872, Charles Marshall had “taken into partnership … William B. Slade, one of the cleverest and most respected of the young gentlemen in the district”; and the Queenslander said in 1932 that “It was Mr. Deuchar who laid the foundation of the noted Shorthorn and merino studs on Glengallan.”

The Marshalls’ substantial investment in Glengallan wouldn’t have been as lucrative as it was without the exceptional skill, hard work, and intelligence of both Deuchar and Slade. As the Brisbane Courier noted in November 1872, Charles Marshall had “taken into partnership … William B. Slade, one of the cleverest and most respected of the young gentlemen in the district”; and the Queenslander said in 1932 that “It was Mr. Deuchar who laid the foundation of the noted Shorthorn and merino studs on Glengallan.”

How different would all their lives have been if John Deuchar and Charles Marshall had been as long-lived as William Ball Slade.

Thank you.

In preparation for her speech, Megan prepared a summary of information regarding the Marshalls and their families. It proved to be too long for the dinner and had to be edited to yield this speech. The longer, more detailed summary can be found HERE.

©Megan Stevens 2018

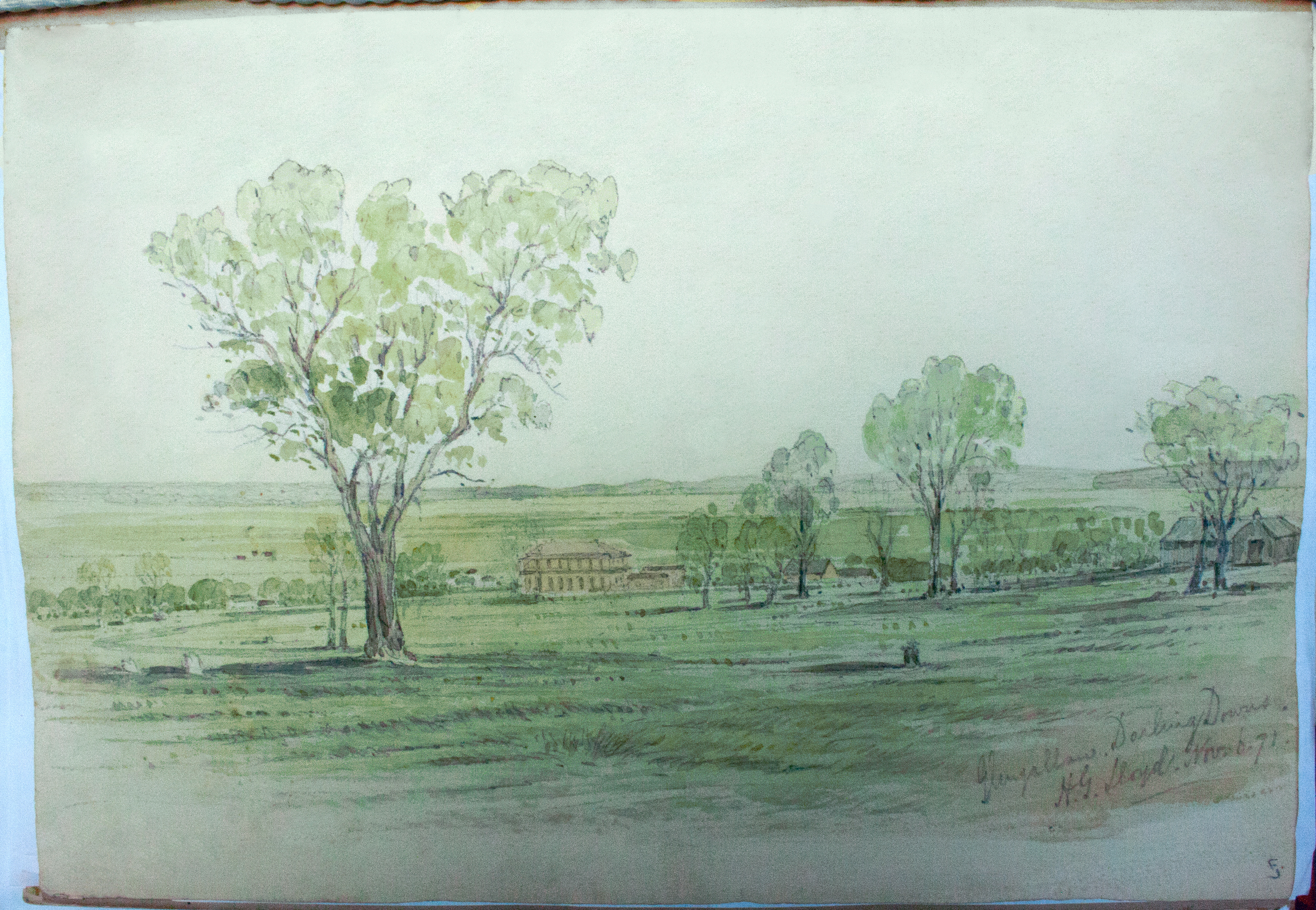

Glengallan Darling Downs, HG Lloyd, Nov 6, 71

Glengallan Darling Downs, HG Lloyd, Nov 6, 71

Thank you for asking me to speak about my great-great-grandparents, Charles and Charlotte Marshall. It is good to be here, near where the “old house” stood, where my great-grandmother was born in 1859.

Thank you for asking me to speak about my great-great-grandparents, Charles and Charlotte Marshall. It is good to be here, near where the “old house” stood, where my great-grandmother was born in 1859. Four years later, William died suddenly, and the Devon families rallied to care for the orphans. His probate poignantly recorded the children’s election of their uncle, John Bentall, as guardian of their inheritance, which secured their futures.

Four years later, William died suddenly, and the Devon families rallied to care for the orphans. His probate poignantly recorded the children’s election of their uncle, John Bentall, as guardian of their inheritance, which secured their futures. The Marshalls’ substantial investment in Glengallan wouldn’t have been as lucrative as it was without the exceptional skill, hard work, and intelligence of both Deuchar and Slade. As the

The Marshalls’ substantial investment in Glengallan wouldn’t have been as lucrative as it was without the exceptional skill, hard work, and intelligence of both Deuchar and Slade. As the