Reminiscences

Young Harold; Harold with his siblings; Harold with fellow RAF officer 1918; Harold with his sister and his plane 1918; Harold in World War II

Megan’s great uncle, Harold Thornton Ayliff (1898-1962), served in the Royal Air Force soon after it was created just before the end of World War I. His brother, Jonathan (Jon) joined him. Three of his sisters, Janet, Charlotte (Charlie) and Megan’s grandmother, Margaret (Meg), were also serving in England and France at the time as nurses in the Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD). In later life, Harold recorded his reminiscences of this period while Charlie, who married a New Zealand soldier and moved to New Zealand, kept an extensive photographic record. Megan has joined the two records. The words explain the photographs and the photographs bring colour to the words – even though they are all black and white.

The reminiscences are much easier to follow with a bit of family and historic context. Harold was the youngest son of Edwin Horace “Horace” Ayliff (1859-1933) and Charlotte Louisa “Louie” Marshall (1859-1937). Horace’s parents, Jonathan Ayliff (1829-1885) and Susannah Wood (1834-1890) were the children of 1820 Settlers. Louie was born on Glengallan, Darling Downs, Queensland to Charles Henry Marshall (1818-1874) and Charlotte Augusta Dring Drake (1838-1922). Detailed family trees and descendant charts for the families can be found here.

|

|

|

Harold Ayliff and his birth certificate. |

|

|

|

|

Harold with his sisters, Meg, Charlie and baby Maud. Walter, Meg, Janet, Jon, Charlie with Harold on right. |

|

|

|

The Ayliff family. Back: Janet, Jon, Charlie, Walter, Meg. Front: Amy, Horace, Maud, Louie, Harold, and Aunt Sarah Ann. |

Reminiscences (Unfinished)

During my last year at school (1917) round about September-November, Major Alistair [sic] Miller brought the first aeroplane to South Africa. This was the Major’s second recruiting tour in this country. He was recruiting for the Royal Flying Corps [R.F.C.] which was a branch of the British Army. South Africans including himself had proved themselves to be exceptionally fine airmen hence the recruiting tours of this country, the first had been in 1916.

Most recruits, including myself, were still at school, & were accepted conditionally on completing the year’s schooling & passing the Matric. In the R.F.C. all pilots were commissioned officers, and the matriculation standard was considered the lowest acceptable.

In January 1918 a R.F.C. medical officer was sent to examine the recruits. The Grahamstown chaps had to go to East London for this test. After passing medically & educationally, we had to wait till advised to report for drafting, some for training in Egypt & some in England. I was sent to England. We sailed in April & arrived in May. By this time the flying services, the R.F.C. & the Royal Naval Air Services, had been combined as an independent branch of the Armed Forces called the Royal Air Force.

We were taken to a Recruiting Depot at Hampstead in London, where we were again medically examined & attested. We were then sent to Hastings, on the South Coast, where we were given intensive military training mostly parade ground work, interspersed with lectures on the theory of flying, military discipline, & the morse code. After passing out we were posted to Denham School of Aeronautics where we were put through a thorough course on aeroplane construction & navigation in theory only although we were allowed to taxi around a field with old machines stripped of most of the wing fabric so that they could not take off. We also had a course on aero-engines, as we had been selected for training as scout pilots we learned the rotary engine.

From Denham [Map] we went to Uxbridge School of Armaments where we had a short course on Lewis machine guns & a concentrated course on the Vickers machine gun as then used on scouting planes.

This completed our ground training. On Saturday 2nd November 1918 we were given two weeks leave, after which we had to report to various air schools for Flying training. I was posted to Redcar on the Yorkshire coast.

During the ground training we had two spots of bother with the authorities. Firstly we all put up “South Africa” badges on our shoulder straps. We were ordered to remove them but stuck together & refused, the Air Ministry relented & allowed all from Commonwealth countries to wear the name of their country. Then we discovered that the new R.A.F. allowed pilots from the rank of Sergeant. We sent a deputation to see Major Miller then in London as we had been expressly recruited as trainees for Officer pilots. It was granted that all Major Miller’s recruits would be treated in the old R.F.C. way & receive commissions on completion of their ground training, in this way as from November 2nd I became a 2nd Lieutenant. It was only later in 1919 that this rank was changed to “Pilot Officer” & likewise all R.A.F. ranks were given their own distinctive ranks.

|

|

South African Air Force Cadets, 1918. |

Of course on November 11th the Armistice was signed & on Nov. 16th I reported to Redcar. The weather there was so bad through that winter that there was very little flying for us trainees. In January all training was cancelled & we were given leave a fortnight at a time. Later on after peace was signed we could take 14 days leave & wire for extension each fortnight. This arrangement was just to keep in touch with us.

I was eventually repatriated leaving England in August & landing in Port Elizabeth in September 1919.

During the foregoing period my best pal was Frikkie Brink (Frederik Neser-Brink). He was in civilian life a mounted policeman. He was quite a bit my senior, when the 1914 Rebellion broke out he, with as many police as could be spared, was rushed as the first line of defence. From the rebellion they went through the South West African campaign, when that was over he volunteered for German East Africa, & finally became one of Major Miller’s recruits. When I was posted to Redcar he went to North Driffield, also in Yorkshire but not on the coast. The only fellow Major Miller recruit with me at Redcar, he hadn’t gone over with our draft, was a chap by the name of Scholtemeyer, also an ex-policeman who gave me to understand that he did not like Frikkie Brink. When I later mentioned him to Frikkie it turned out that he had been one of a batch of rebels taken prisoner by Frikkie’s crowd & Frikkie used to make him responsible for cleaning his (Frikkie’s) boots & saddle.

Also in England at that time were:- my eldest brother Jon who had later joined up for the R.A.F. & was still in the ground training stage; my sister Charlie who had gone over in 1913 to study art in London; & my sister Meg who had joined up as a nursing V.A.D in S.A. & after serving out here had been drafted to an S.A. Hospital in France. When I got leave from Redcar I went first to Driffield & found Frikkie all ready to go on leave so took him with me, we went to London & stayed at the S.A. Officers Club [Map]. I contacted Charlie who was nursing at a New Zealand Hospital at Walton on Thames. Her great friend at the Art School had been the daughter of the High Commissioner for N.Z. & when she decided to join the N.Z. nursing services Charlie went with her. When I contacted Charlie she said she could get leave, I managed by using my rank to wangle leave for Jon. We were all going to concentrate at our Grandmother’s house in Redhill, Surrey.

Meg happened to get leave with her friend Beery (Nurse de Beer). She contacted Charlie who told her of the arrangements & that she could find me at the S.A. Officers Club. This she did & met Frikkie also. A day or so later she ran into a cousin of ours Clive Marshall, a private in the Australian Infantry. I had met him but Frikkie & he had not met.

|

|

Carrots (Harold) Ayliff and Frikkie Brink. |

|

|

|

Charlie (standing second from right) with Leonard Walker’s sketching class, 1913; at St. Ives, 1913. |

|

|

|

|

Charlotte Ayliff paintings. Her sister Meg signed ‘CA’. Still Life signed ‘CT’ [Charlotte Taylor]. Click to expand. |

|

|

|

|

|

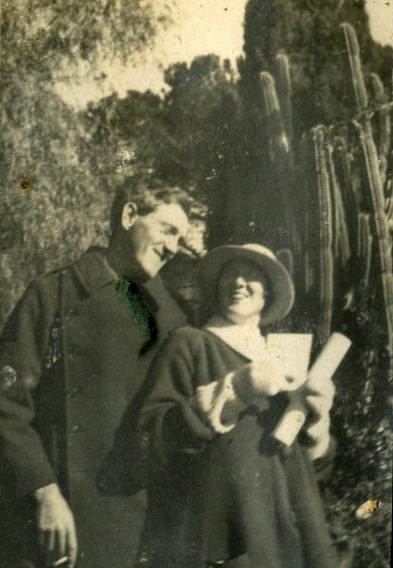

Charlie, with Sister Nutsey at Inversnaid, and with Carrots. |

||

|

|

|

|

Harold, with Charlie. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

Jon Ayliff. (Third from the cox.) |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Meg and Beery – and the VADs (with Janet and Charlie too). |

||

|

|

|

|

A young Hawtrey Marshall; and Clive Marshall. |

||

Meg & Clive came to get hold of me at the Club. Meg asked Clive to ring & ask the doorman for me, I was out so she told him to ask for Lieut. Brink. Frikkie came out, saw Meg in the taxi but before he went to her a strange Aussie jumped to the salute. Frikkie grabbed his hand & shook it saying “Put it there, you are the first Aussie who has ever saluted me.” I am afraid Clive never forgave Frikkie for that, even when they both formed part of the gathering at Grannie’s House.

Grannie was more or less confined to her bedroom & how she put up with our crowd the lord alone knows, but she seemed to enjoy it all. Our Uncle Hawtrey, an ex-Regular Army Major, then on the retired list but holding some job in the War Office, was there on leave too & a very good sport he was also.

Every morning he would finish his breakfast with a slice of toast & butter followed by a slice of toast & marmalade. Charlie asked him why didn’t take both butter & marmalade together on the toast. He replied “I am afraid I do not believe in economising.” Charlie asked how that would be economising he replied “Think how much more toast I can use eating my butter & my marmalade separately.”

Meg had an ex-patient Farquason (I’m not sure of the spelling), his nickname was Hertzog (I don’t know why). He called at Caberfeigh (Grannie’s House) one day when we were at lunch. Poole the parlour maid answered the bell & came in & announced “Mr. Hertzog to see you Miss Meg.” Uncle turned round & said to Meg “I didn’t know you were friendly with the General!”

Later when Charlie had been demobilised & was to return home, I went to see her off at Waterloo Station, she was catching the boat train to Southampton. I arrived at the station but could find no sign of her. In one corner of the station was a bit of a crowd apparently highly amused. I thought it was some soap box orator or other. Eventually I decided to while away my time by listening also. Imagine my surprise to find the cause of the laughter was Charlie. She had tons of luggage to which she was affixing the usual ship’s labels. She had a wartime miniature porter about 13 years old standing in front of her, with his tongue out & she was damping the labels by rubbing them over the tongue. When she saw me, she exclaimed “Oh Carrots, I am glad to see you, this porter has just about run dry.” She was most indignant when I sent the porter for a fire bucket of water, instead of hanging my tongue out.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grannie Marshall, and her home, Caberfeigh, Redhill. Marshall ancestors on the wall. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Jon Ayliff; Uncle Hawtrey Marshall, Meg, Clive Marshall, and Beery at Caberfeigh. |

|

|

|

Carrots, Beery, and Meg (in cockpit) with Avro 504 trainer. Click to expand. |

I had been spending a lot of time visiting Charlie, & spending her off hours on the river together. She used to take me along to chat to her special patients. The one I remember most had been blown into the air by shell blast & come down with his head cracked in the seam from his forehead to the base of his skull at the back. The doctors had been unable to get the bone to knit & he wore a sort of skull cap, made of rubber. He was a very intelligent fellow, could converse on practically any subject, used to read, write & paint, but in the six months he had been there he had never slept a wink. Years later Charlie ran across him in New Zealand & he had still not slept. I spent many hours chatting to this chap & really enjoyed every minute of it.

Charlie when she first ran across him was on night duty. The night staff used to go at midnight to the common room for cocoa & buns, of course someone had to stay on duty in the ward & others would bring for them. Charlie started cadging an extra mug of cocoa & a bun for the sleepless patient & he much appreciated it.

When she was moved to another ward she asked her relief nurse to carry on the good work, but this nurse refused as it was against regulations, so Charlie got cocoa & bun & took it to him. The other nurse reported her for interfering in their ward. The Matron would not hear of Charlie’s explanation & punished her by stopping her days off. Charlie appealed to the Hospital O/C. When he heard what Charlie had to tell, he was most indignant & said that Regulations are made for the general run of cases but that there were always exceptional cases & this was one of them. & he gave strict orders that in future this patient must have his cocoa & bun every midnight.

|

|

|

Harold after an accident in Port Elizabeth, June 1920; and at his wedding with his wife, Gladys Rubidge, 1923. |

|

|

|

|

Harold, with his two eldest daughters, Nova and Doreen. |

|

In 1939 I was stationed at Naauwpoort (now Noupoort) as a driver on the R.M.T. services. I heard that a service was to be opened between Port Elizabeth & Grahamstown, I applied for it & was lucky to get the appointment.

In September of that year war was declared & recruiting was opened for the P.A.G. [Prince Alfred’s Guard] I was the first R.M.T. Driver to volunteer, having done so I handed a letter to the Driver-in-charge (Rheeder) informing him of this fact. He was very opposed to the war effort, & told me that I had no right to volunteer without first writing in and obtaining permission from the System Manager’s office to do so. I said I did not read the circular that had been issued in that way. I took it that we must first volunteer & then ask to be released. He disagreed with me & said he would not forward the letter. I told him he had no authority to withhold the letter & that to be on the safe side I would post a copy of the letter to the System Manager with a covering letter. I didn’t need to do this of course, but when the reply came back, the head office stated that they were not interested in the fact that I had volunteered, but that when I had been finally accepted by the army I should apply to be released. This I eventually did, but the P.A.G. was not called up on full time service until October 10th 1940.

In the mean time we had part time training in the evenings, normally twice a week. So as to be free for this part time training & for immediate release when required, I was taken off the country service & put on to the suburban services (Walmer & New Brighton).

I was put on the strength of 13 Company of the P.A.G. Our company commander was Major Reg Rice, a very fine man. I had to produce my discharge certificate from the R.A.F. He promptly wanted to appoint me to commissioned rank. I refused as being a Railway servant, the difference between my Civilian pay & my Army pay would be paid to my wife, so the lower my Army pay was the better off the family would be. I told him that from my point of view the ideal rank was Lance Corporal, where I had practically no responsibilities, but got out of fatigue & guard duties. He promptly made me a Lance Corporal & that was the highest I ever went in the 2nd World War.

When the so called Red Tab oath was brought out – the defence force oath was to defend the borders of the Union – we then took an oath to defend our country wherever required & having taken this oath we wore red tabs on our shoulders. We were marched one evening on to the Donkin reserve, our officers then went around taking the names of those prepared to take the new oath. Our platoon officer was Lt. Dan Brown & he took our names. In our section was a young chap, Stolz. He could speak very little English. The fellows were discussing where we would go, Kenya, Abbysinia [sic] & Egypt were mentioned, but mostly the last. This chappie came to me & asked “Korporaal, wat is die ding Egypt.” [Corporal, what is this thing, Egypt.] I explained as best I could. He ran off after Mr. Brown shouting “Krap my naam dood, krap my naam dood.” [Scratch my name out (dead).] I never saw him again.

During this time, a practice started throughout the Country which lasted till the end of the war. At 12 noon each week day people, vehicles & everything in town would stand still for 2 minutes pause. Soon the opponents of the war effort, usually referred to as the O.B. [Ossewabrandwag (Ox wagon piquet/guard) – a sometimes violent Afrikaner, anti-British organisation], although not necessarily belonging to that organisation, started trying to break up the pause, special efforts were made on Saturday. It culminated one Saturday in a tremendous riot in Main St, P.E. [Port Elizabeth] Cars were turned over, including a police van. Fighting broke out & there were a lot of arrests. It so happened that I had to drive the 12 o’clock bus from Griffin St. to Walmer that day. At the end of the pause, signalled by a bugle call, I started up & moved round the corner into Main Street, & arrived at Castle corner at twenty five to one, such was the mix up in the street. When I got to Walmer I was met by our despatcher just about tearing his hair out, wanting to know where I had been all the time & where were the rest of the following buses. I advised him to go & look at Main street for himself.

Some idea of the bitterness & mentality of the O.B. group can be seen from the following incident which is absolutely true.

I think it was a Monday, but a partial eclipse of the sun was predicted for that day & it duly happened. [The only eclipse affecting Port Elizabeth in this time period was on Tuesday 1 October 1940.] Round about 8 am on weekdays there used to be an accumulation of 3 or 4 buses at 6th Avenue Walmer to clear the business rush, each would move off at his appointed time & others would come. One driver (Henry Potgieter) was very bitter, his conductor was young & rather ignorant. One of the others asked him if he was going to watch the eclipse & this is what I heard him say “Daar is nie sulk ’n ding as ’n “eclipse”. Henry sê dis net Britse propaganda.” [There is no such thing as an eclipse. Henry says it’s just British propaganda.]

The regiment was withdrawn back to South Africa in early 1943 and retrained as a tank regiment as part of the South African 6th Armoured Division. They returned to North Africa and in April 1944 landed at Taranto, in the heal of Italy, as part of the 8th Army. They were then part of the campaign that moved up the west coast of Italy via Monte Cassino through Rome to the Po Valley and the final German defensive position, the Gothic Line. This is where they were when the war ended in May 1945.

Extract from Harold’s letter

31 December 1944

Well this is a wind up of my reports on my leave in Rome, although unfortunately I am no longer there … It is impossible for me to describe things as I am not up in art to discuss the wonders of painting sculpture and architecture I saw, in fact I saw so much that I afterwards hardly knew what I had or had not seen. One morning we spent in the Vatican Museum, suffice it to say it is breathtaking … At the Castel St. Angelo which was first a mediaeval castle and later a pope’s residence I saw ancient catapults for throwing javelins and huge balls of stone, also devices for pouring boiling oil and lead on the enemy, to say nothing of such delicacies as secret trap doors for dropping one on to knife blades etc. St. Pauls – outside the Walls is a very beautiful church and the second largest in Rome. But the church which struck me most was St. Mary of the Angels, outside it is part of the ruin of some ancient Roman baths, inside a most beautiful church, designed by Michael Angelo … What did strike me was the fact that all these big churches provide for no, or practically no seating accommodation, the congregation being expected to stand. This was demonstrated at St. Peter’s at the midnight mass on Xmas eve … It is estimated that over 5 thousand people were in the church and more than double that number were unable to get in. I went with the 2 ladies I had met, Signora Collotta and Signora Pocchioni. The latter’s husband did not go. The ladies intended partaking of mass but it was impossible. I went expecting to see and hear a very solemn service, I also was disappointed. The crowd was milling and pushing, all the time jockeying for vantage points. Parties getting separated were shouting at each other, some hooligans found much fun in starting to push, causing people to get jammed up, women getting squashed would scream, and several fainted, the Yanks were chewing their eternal gum, people were climbing on to the statues to see and the top of every confessional was covered with people. Luckily being tall I could see most of the service but it was impossible to hear anything except the singing of the carols by the choir. Then to cap all, flashlight photos were being taken of the pope performing the most sacred rite of the church.

(From Jean Taylor, 10 December 2000)

|

|

|

|

|

Harold Ayliff, in Egypt. |

|

|

|

Lance Corporal Harold Ayliff, Prince Alfred’s Guard. |

MAN WITH SETTLER LINK DIES

Herald Reporter

The funeral of Mr. Harold Thornton Ayliff, a 63-year-old great-grandson of an 1820 Settler, will take place in Uitenhage today. Mr. Ayliff died on his daughter’s farm in the Elands River Valley on Tuesday. His Settler ancestor was the Rev. John Ayliff.

SECOND

He was the second youngest of nine children and is survived by five of them: a brother in Johannesburg, two sisters in Grahamstown, another in Cape Town and a fourth living in New Zealand.

Mr. Ayliff was educated at Kingswood College. He volunteered to serve with Major A. Miller, the South African flying pioneer, in the Royal Flying Corps. He took part in the final months of Worth War I.

P.A.G

In World War II, Mr. Ayliff served with Prince Alfred’s Guard and the Natal Mounted Rifles.

Between the wars he tried his hand at farming, before joining the S.A. Railways. He was a member of the M.O.T.H. association.

His widow, Mrs. Gladys Ayliff, is a descendant of the Rubidge 1824 Settler family of Graaff-Reinet.

Mr. Ayliff leaves a son, Mr. Sydney Ayliff, and three daughters, Mrs. Nova Coetzee, Mrs. Doreen Els and Miss Lola Ayliff, a 21-year- old teacher in Port Elizabeth. He is also survived by six grandchildren.

The funeral service will be held at the Uitenhage Congregational Church, Caledon Street, at 11 a.m. today.

The M.O.T.H. Association is the Memorable Order of Tin Hats Association and is a service organisation for ex-servicemen and women.

©Megan Stevens 2021

This is so interesting. Many things I never knew about the Ayliff family members & some of the Marshall’s.

I even see mum’s name.

XOXOXO

Thankyou cousin’s for this. XOXOXO

Thanks, Judith. Harold’s story is just wonderful – and fits in so well with the photos taken by your granny at the time. It just felt right to put them together like this. Lots of love, M.