The Marshall Orphans

William Marshall; Table Bay, Cape Town c1811; St. James Cathedral, Mauritius; 37 Craven Street, London; Leith Postal Directory listings for William Marshall for 1823 to 1827; Certificates for annuity bonds; Signatures of the children electing John Bentall as Curator and Guardian; Buckfast Abbey manor house; Louisa Marshall (née Bentall).

Charles Henry Marshall and his siblings had an eventful early life. Their parents, William Marshall and Louisa Bentall, married in 1810, just prior to moving to Cape Town where they had four children. They then moved to Mauritius where they had five more children. Only six of the children lived to adulthood, and the family story was that three of those born in Cape Town, Mary, John and Charles, died as infants.

Louisa died in 1823 in Mauritius, after which the family relocated to Leith, Scotland, where William also died in 1828 without leaving a will. The family stories were that this left the children destitute and that they had to be supported by their wider family – especially the Benthalls. (The Bentalls changed their name to Benthall in 1843 so the spellings are interchangeable.)

Although he died intestate, William’s estate required administration and probate, and the probate documents reveal a very different story from that which passed down through the family. The information prompted and focused further research which revealed more information about their time in Cape Town and Mauritius, their return to England, and the support they received from their wider family following their father’s death. We also came into contact with Tim Benthall who was researching his family including the Benthall’s interaction with the Marshalls so we had a lot of common points of interest. He also had a number of valuable family records that provided a lot of insight. We would not have been able to present this picture of the family without Tim’s help.

The probate documents

Whilst much of the story occurred prior to William’s untimely death, the probate documents 1 provide a good starting point because they introduce a number of the key players in the children’s lives. They also elucidate the children’s circumstances following their father’s death, and the arrangements that were put in place for their care, which set the scene for their adult lives. The documents are presented below. The first three pages are the Probate Declaration by John Bentall, Louisa’s brother, who took on the administration of the estate on behalf of the children. He was a stockbroker living at 37 Craven Street, The Strand, London: a man with clear financial credentials to oversee the children’s inheritance.

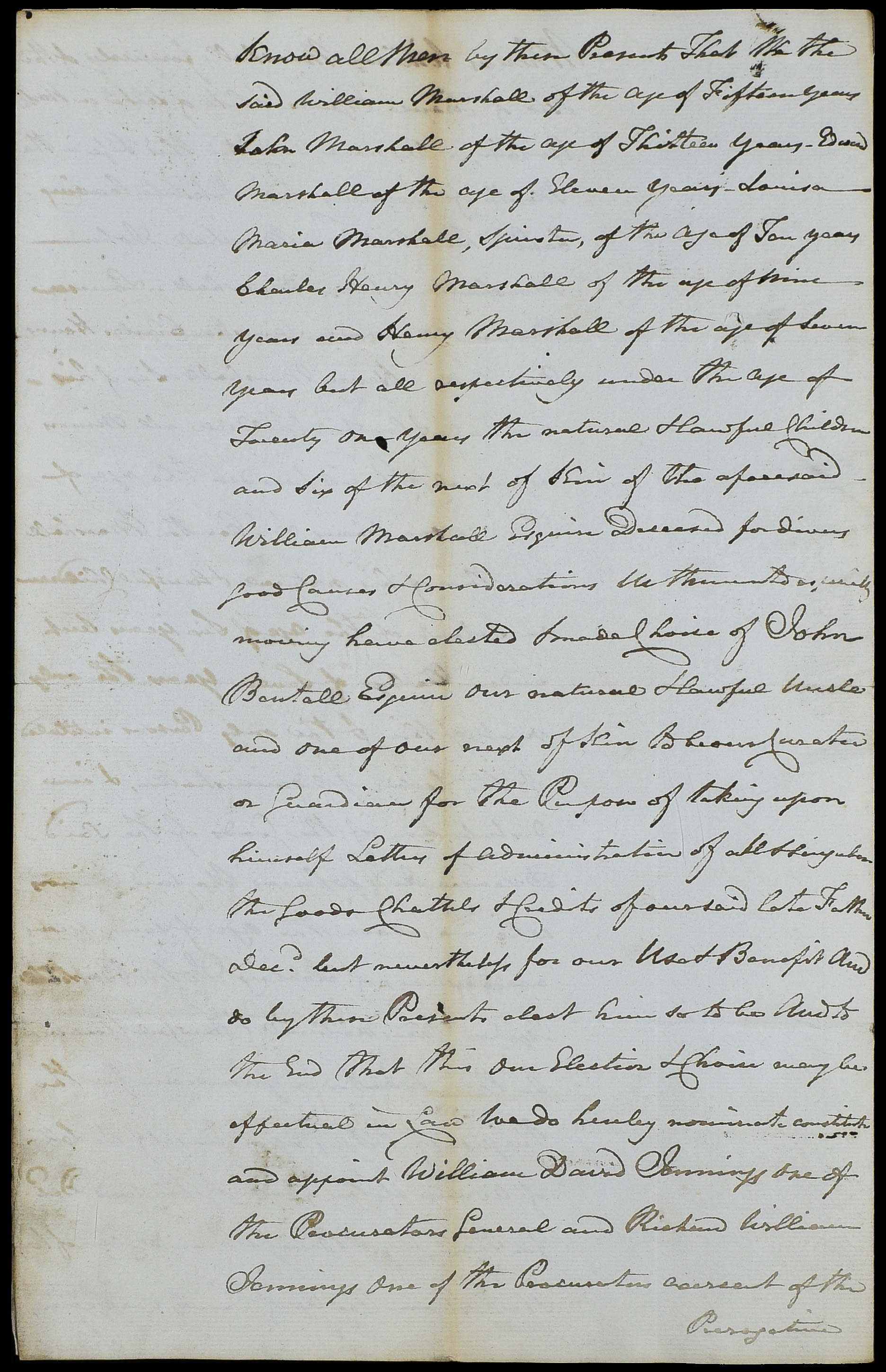

Uncle John was not just appointed to the administration of the estate. He was in fact elected by the six eldest children to be the Curator and Guardian of their financial interests in the estate. This is laid out in the second set of three pages, which is the Proxy by which the children, who were all under age, effected this nomination with the assistance of an officer of the court. The signing of this deed and its witnessing give further insights into the involvement of the wider family in their welfare.

These images are provided by and published with the permission of The National Archives whose copyright position can be found

|

513

Willm Marshall Proxy & Decln Brot in 12 April 1828 |

| Cover – The National Archives |

|

In the Prerogative Court of Canterbury In the Goods of William Marshall Esqre deced A Declaration instead of a full true plain

|

||||

| Declaration Page 1 – The National Archives |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Declaration Page 2 – The National Archives |

|

Lastly this Exhibitant declares that no further

Before me, |

|||||||||

| Declaration Page 3 – The National Archives |

The lack of a will suggests that William died suddenly and that, because of his relatively young age, had not yet deemed it necessary to make a will. The amount of the legacy, however, indicates that he was a prudent and financially aware man. John Bentall’s declaration shows that the estate comprised £72 of cash, £1,790 of Government securities, 2 and £110 of personal items including jewellery, linen and silver plate. £1,862 of financial assets was a substantial sum at the time. It is very difficult to determine what a comparable value would be today, but if we compare £1,862 to average incomes at the time and calculate what sum would similarly compare to average incomes today, the value is £1.5 million. Using a cost of living index (which, for technical reasons, tends to understate the comparative value), the value today would be £151,000. A healthy legacy whatever the conversion method.

|

Whereas William Marshall formerly of the Know |

| Proxy Page 1 – The National Archives |

|

know all then by these Present that We the Prerogative |

| Proxy Page 2 – The National Archives |

|

Arches Court of Canterbury to be our Proctors 3 tenth day of March 1828

|

||||||||||||

| Proxy Page 3 – The National Archives | |||||||||||||

|

Sealed & delivered by the said John Marshall Samuel Adams of Hounslow Gentleman. |

| Proxy Page 3 Insert – The National Archives |

The first thing we noted on the Proxy, was the signature of John Marshall. He clearly had not died at the Cape, but, as he did not reach adulthood, what happened to him? This will be discussed later.

The Proxy is a poignant document with the signatures of William (aged 15), John (13), Edward (11), Louisa Maria (10), Charles (9), and Henry (7) neatly made beneath each other, the writing style moving from William’s mature script to Henry’s shaky childish writing. This would undoubtedly have been a daunting experience for them so soon after their father’s death, despite the process being overseen by their uncles.

The execution of the document by the children and the witnessing of their signatures indicate that they were living in three different places. The signatures of John, Edward and Henry were witnessed by Samuel Adams of Hounslow, London, and one of his servants, Elizabeth Varder. Louisa Maria’s signature was witnessed by Richard Collins and his son, John, in Exeter, Devon. William’s and Charles’s signatures were witnessed by William Dacres Adams and Henry Bentall Adams in London. It seems likely that William and Charles were living with their uncle, John Bentall, who was not able to witness the deed as it was in his favour. It is unclear where Thornton was living when the deed was executed, but it seems most likely that he was with his sister, Louisa Maria, with the Collins family in Exeter.

The signature block for William and Charles is also interesting in that the names of John, Edward and Henry are crossed out and a separate insert is made on the document to accommodate their witnesses. It would seem that it was intended that they too were to stay with John Bentall, but they instead went a little further out of London to stay with Samuel Adams at the Hounslow Cavalry Barracks.

Who were these people and why were they the ones taking care of the children? The answer to these questions can best be explained by looking back on how the children came to be in this situation.

Background

In 1810 the shoreline was where the train tracks are now

1788 Cape Town Panorama

William Marshall and Louisa Bentall were married on 16 February 1810 at St Mary’s in Totnes, Devon. William was 30 years old and Louisa 27. The witnesses to their marriage were Wm Bentall (Louisa’s father), Elizth Adams (Louisa’s sister and wife of Samuel Adams), Wm Adams (M.P., Elizabeth Adams’s brother-in-law), W. S. Bentall (William Searle Bentall, Louisa’s brother), and Wm Bentall Jr (William Searle’s son). The couple then moved to Cape Town where William took up the position of Assistant Deputy Paymaster General to the Cape Garrison, arriving in October 1810. They bought a house at 5 Buitenkant Street, which is just up from the Castle, and lived there until mid 1816. They had four children during this period. Two, Mary and Charles, died as infants, but William (born 1812) and John (born 1814) survived.

William was then transferred by the army to Mauritius where he served as Assistant Deputy Paymaster General until April 1817. He then became Commissaire Général de Police (Commissary-General of Police), a rank equivalent to that of Superintendent. This followed the creation of a Corps of Gendarmerie in 1816 which, for linguistic reasons, shared command between a British and a French officer. William was in joint command with M. Journel [search for Journel]. He remained in this position until June 1818.

It is not clear how he supported his family after leaving the police, especially because he had suffered a significant financial loss due to a failed investment. Whatever the financial arrangements, the Marshalls remained in Mauritius and five more children were born there – Edward (born 1816), Louisa Maria (born 1817), Charles Henry (born 1818), Henry (born 1821) and Thornton (born 1822).

William then returned to Britain and established himself in Leith, Scotland, where, in the Post Office Directory for Edinburgh and Leith, dated 18 May 1823, he is listed as a merchant. With travel times from Mauritius (generally 4 to 5 months – the quickest being 3 months), setting up business and registering with the directory this means that he would have had to have left Mauritius by no later than sometime in January 1823 and probably even earlier – i.e. prior to his wife’s death.

His two eldest sons, William and John, preceded him. They went to England to attend school, most probably during 1821. On 26 September 1821, Mary Ann, wife of William Searle Benthall and the boys’ aunt, commented in a letter that the two boys had returned to Totnes. Both were described as “very pleasant children,” with William attending Totnes Grammar School as a boarder, and John living with the family. 4

William and John also attended a function in Totnes for the 80th birthday of their great aunt, Dorothy Marshall (neé Chadder), on 29 August 1822. Their attendance is recorded on a fascinating document containing the names of the attendees, signed at the function. Photography wasn’t available at the time so we refer to this as the ‘analogue photograph’. Whilst it is a slight diversion from the narrative regarding the orphans, I am showing it in full with a transcript, because it demonstrates the extensive, interlinked family that featured prominently in supporting the orphans:

On Thursday the 29th August 1822 We the undersigned Children and Grandchildren of Mrs Marshall, being in all forty persons, were assembled in her presence and in that of Mrs Baker her sister, in the house of William Searle Bentall, Mary Bentall, Thornton Bentall and Margaret Bentall who have there resided as one family since the month of April 1810.

| Elizth Cornish W F Cornish |

Willm Marshall I.C.C.O. Marshall X The Mark of Clementina Marshall X The Mark of Caroline Marshall X The Mark of Emily Marshall |

Richd Marshall Sally Marshall William Marshall Jane Marshall Ellen Marshall X Louisa Marshall X Mary-Ann Marshall X Margaret Marshall their marks |

J Marshall J. Marshall F. O. Marshall Emma Marshall X Mark of Wm. Ord Marshall A Mark of Anna Marshall |

E Marshall | M A Bentall W S Bentall William Bentall Elizth Bentall John Bentall Edward Bentall Anna Bentall Henry Bentall Alfred Bentall T. Bentall Francis Bentall mark of Octavius Bentall X mark of Louisa Bentall X mark of Ellen B Bentall X |

S Marshall | A G Marshall | M E A Bentall Thornton Bentall |

|

Witness D Marshall Aged 80 E Baker Aged 87 E Cornish Peggy Ford B Earles S. C. Ogilvie M W Coombe Sarah Drewe Wm Marshall L Borrow J Marshall |

Signature of Mrs Marshall’s Great Great Nephew William Fulford |

|||||||

Notable signatures on the bottom left are Dorothy Marshall aged 80, Elizabeth Baker aged 87 and, at the bottom below them, John Marshall with William Marshall two above him. Elizabeth Baker was actually Dorothy Marshall’s sister-in-law.

The top row of signatures is of Dorothy Marshall’s children with each of their spouses beneath them and then their children. [Dorothy’s and William’s family chart.]

1: Elizabeth Cornish (née Marshall) (1772-1862), Rev. William Floyer Cornish (1769-1858).

2: Rev. William Marshall (1774-1864); Isabella Carolina Clark Ogilvie Marshall (née Perry Ogilvie) (1792-1833); Clementina Marshall (later Benthall) (~1818-1905); Caroline Mary Marshall (1819-1894); Emily Marshall (later Johnson) (~1820-1895)

3: Dr. Richard Marshall (1776-1859); Sally Marshall (née Ford) (~1776-1858); William Marshall (1807-1885); Jane Farwell Marshall (~1809-1865); Ellen Marshall (~1811-1828); Louisa Marshall (later Edgcumbe) (~1812-1880); Mary Ann Marshall (later Thompson) (~1815-1855); Margaret Marshall (born ~1817) [Family chart.]

4: John Marshall (1777-1850); Jane Marshall (née Campbell) (~1790-1868); Francis Ord Marshall (1810-1870); Emma Jane Marshall (later Venning) (~1813-1878); William Ord Marshall (~1816-1892); Anna Jane Marshall (later Dumergue) (~1815-1884)

5: Edward Marshall (~1779-1868)

6: Mary Ann Bentall (née Marshall) (1780-1866); William Searle Bentall (1778-1854); William Bentall (1803-1877); Elizabeth Bentall (later Waterfield) (1804-1886); Rev. John Bentall (1806-1887); Edward Bentall (1807-1889); Anna Bentall (later Gay) (1809-1874); Henry Bentall (1811-1879); Alfred Bentall (~1813-1839); Thornton Bentall (later Thomas Bennett) (1814-1898); Francis Bentall (1816-1903); Lieut. Octavius Bentall (1818-1846); Louisa Bentall (1820-1859); Ellen Blayds Bentall (later Younghusband) (1822-1865) [Family chart.]

7: Sarah Marshall (later Hamilton) (1783-1849)

8: Ann Gowan Marshall (~1784-1835)

9: Margaret Eleonora Admonition Bentall (née Marshall) (1787-1860); Thornton Bentall (1781-1844)

Witness: Dorothy Marshall (née Chadder) (1742-1828); Elizabeth Baker (née Marshall) (1735-1825); Elizabeth Charlotte Cornish (later Bentall) (~1804-1871); Peggy Ford (~1778-1854); B Earles; Sarah Christiana Keightley Perry Ogilvie (1798-1880); M W Coombe – Governess; Sarah Drewe; William Marshall (1812-1901); L Borrow – Governess to Richard and Sally Marshall’s children; John Marshall (1814-1831);

Major William Fulford (1812-1886)

Father William was not recorded as being present at the function so had either not yet arrived from Mauritius or had already moved to Leith, leaving his sons in Totnes for the school holidays.

Louisa died on 24 March 1823 – probably due to the cholera epidemic then sweeping Mauritius. There is no information on who cared for the remaining children, but they stayed in Mauritius for another year before returning to England. Shipping records show that “Miss Marshall” and “four Masters Marshall” arrived from Mauritius on board the Hero of Malown, docking at Falmouth on 5 June 1824. 5 A letter written from John Benthall’s residence in Craven Street, Westminster, by Thomas Peregrine Courtenay, the Member of Parliament for Totnes, to Thornton Benthall (John’s brother), on 8 June 1824 confirms this and the family’s concerns about the care of the children: 6

On my arrival here after a most tiresome Dusty journey I was greeted with the intelligence that all William Marshalls children would probably be in London in a few days as Mrs. Jennings has received a letter from their father to that effect John[a] is most disconcerted as Mrs. Garfield [?] cannot possibly accommodate them I shall write to Hounslow on the subject today and if I find that your sister[b] does not wish to have them there I have made up my mind to take the whole of a Coach which carries six inside and set off myself with all the family as soon as they arrive but I cannot help having some hope that the Captain of the Ship will have sense enough to send them immediately to Totnes, the poor dear children have only a Negro woman with them and what we are to do I cannot imagine I am afraid that Mary[c] will be completely overcome with all this additional anxiety – Old Mr. Waterfield and his son[d] came to call on me last night and found me as you may suppose rather nervous for I had received eight letters in addition to [illegible] They were uncommonly kind and offered to take some of the children but I cannot impose any more on their good nature.

[a] John Benthall.

[b] Samuel Adams and his wife, Elizabeth, lived at Hounslow. Elizabeth was the sister of John, Thornton, and Louisa Benthall.

[c] Thomas Peregrine Courtenay’s daughter, Mary (born 1811).

[d] Thomas Nelson Waterfield (1799-1862), who later married Thornton Benthall’s niece, Elizabeth Benthall (1804-1886), on May 17, 1826.

Thomas Peregrine Courtenay (1782-1841) is an interesting character in the context of the Marshall story. He was a contemporary of William’s and it seems likely that he attended Exeter Grammar School with William for part of his schooling. William’s father, Rev. John Marshall, was the headmaster, while Courtenay’s father, Right Rev. Henry Reginald Courtenay (1741-1803) was the Bishop of Exeter.

In 1810, when William and Louisa Marshall went to Cape Town, it is probable that William obtained the posting from Thomas Peregrine Courtenay, because, at the time, Courtenay was Deputy Paymaster for the Forces within Treasury and controlled appointments throughout the Empire. Courtenay succeeded William Adams (1752-1811) as M.P. for Totnes in 1811 with the support of the intermarried Adams, Benthall and Marshall families who controlled the Corporation of Totnes – the so-called “Adams-Bentall-Marshall interest.” His brother, Sir William Courtenay (1777-1859), was the M.P for Exeter and in 1835 succeeded his second cousin as 10th Earl of Devon and thereby inherited the Powderham estate – which the Drakes and Marshalls visited 22 years later when touring Devon.

We see a group of mutually supportive, interlinked families from Totnes. They were already involved and interested in the welfare of the children prior to William’s death, but when he died, they went into action to support them.

Caring for the orphans

Let us now consider the names on the Proxy in more detail. Samuel Adams was an uncle as he was married to Elizabeth, Louisa Bentall’s sister. He was a brother of William Adams who had preceded Thomas Peregrine Courtenay as M.P. for Totnes. At that time, Samuel was barrack-master in Hounslow, London. Elizabeth Varder was a trusted servant who served the Adams family until her death in 1862, aged 86. 7 She would undoubtedly have cared for the boys.

Henry Bentall Adams, in London, was Samuel’s son, and a cousin of the children. His fellow witness, William Dacres Adams, was the son of William Adams M.P., a cousin of Henry Bentall Adams and second cousin once removed of the children. When he witnessed the signatures, he was Commissioner for Woods and Forests and had been Private Secretary to William Pitt (the younger) when Pitt was Prime Minister.

We see a number of Adams’s involved and a number of Benthalls, but no Marshalls. This might look strange, but it wasn’t. The reason was simple, but sad. William’s parents, all his brothers and all but two of his sisters had predeceased him as shown on William’s birth family chart. The Marshalls, however, were not absent.

One surviving sister, Anna, was the widow of Rev. Richard Buller, Vicar of Colyton in Devon. The other, Elizabeth (Eliza), was the third wife of Philip Furse and had no children of her own. Richard Collins, a successful merchant in Exeter, was the widower of William’s late sister, Mary. He was the children’s uncle, and his son, John, their cousin. Mary was not alive to help, but her family was, so they did.

Once affairs were settled, the children went to live with their “Uncle Benthall”, William Searle Benthall, who was married to Mary Anne Marshall, William’s cousin – the family with whom William and John Marshall had lived when they returned from Mauritius to go to school. William Searle’s brother, Thornton, was married to Mary’s sister, Margaret Eleanora Admonition Marshall (just how she got the name Admonition, we do not know). At the time of William’s death, William Searle and Thornton Benthall co-owned Buckfast Abbey and the spacious manor house there.

|

|

|

| 1828 showing ruined Abbey 8 Postcard Megan Stevens |

Today incorporated into rebuilt Abbey. Front and back. Buckfast Abbey |

|

They also had extensive property holdings at The Plains in Totnes and jointly occupied their house there – as indicated on the ‘analogue photograph’.

|

|

| The Plains, Totnes, with the William Wills memorial. The Benthall house is behind the trees on the left in the second photo, overlooking the River Dart. ©Alun Stevens 2016 |

|

This is the environment into which the children moved.

William John Wills, of Burke and Wills fame, was born in the house to the right of the memorial on 5 January 1834 – only a few years after the Marshall children moved to Totnes. He died in 1861 in the interior of Australia and his father, William Wills, published a book in 1863 based on his son’s letters and journals. The opening paragraph contains the following regarding the young William John Wills:

About the time of his completing his third year, Mr. Benthall, a friend and near neighbour, asked permission to take him for a walk in his garden. The boy was then in the habit of attending a school for little children, close by, kept by an old lady. In less than an hour, Mr. Benthall returned to ask if he had come home. No one had seen him, and we began to be alarmed lest he might have fallen into a well in the garden; but this apprehension was speedily ascertained to be groundless. Still he returned not, and our alarm increased, until his mother thought of the school, and there he was found, book in hand, intent on his lesson. He knew it was the school hour, and while Mr. Benthall was speaking to the gardener, had managed to give him the slip, passing our own door and proceeding alone to the school, on the opposite side of the square. Mr. Benthall, who can have seen or heard very little of him since, was one of the first, on hearing of his recent fate, to send a subscription to his monument, about to be erected at Totnes. Perhaps he remembered the incident.

“Mr. Benthall” was William Bentall (1803-1877), the eldest son of William Searle and Mary Anne Benthall. He was mayor of Totnes at the time subscriptions were being sought for the memorial.

The children’s Marshall aunt, Eliza Furse, clearly also helped over many years. The 1851 Census shows Louisa Maria Marshall, Charles’s sister, living with Eliza at her home, High House, Kenton also called Kenton Cottage, which is a short walk from the Courtenays’ Powderham Castle. In 1857, when Charles and the Drakes went to Devon prior to his marrying Charlotte Augusta Dring Drake, they visited Eliza and Louisa Maria was still living with her.

We see from this that the families who worked together to control business and politics in Totnes also worked together to look after the children – with the Marshalls represented by their women.

We also found the true story regarding John Marshall. The records show, sadly, that he only enjoyed the family’s support for a few years. He died in Totnes and was buried there on 13 June 1831 – aged 17.

Conclusion

By the time he was ten, Charles Henry had travelled the world and suffered a great deal of family upheaval. His father, however, had provided him with a good legacy and he was taken in by the financially, politically, and commercially connected Benthall and Adams families. This was quite probably the background to another family story that each of the boys was given £50 and sent off to seek his fortune. The size of Charles’s legacy suggests that he went into the world with more than just £50 and the “Return of Tenants, Circular Head” for the Van Diemen’s Land Company for 31 December 1843 would seem to confirm this because Charles, and his brother, Henry, are both listed with the note “has capital” against their names. 9

Charles’s early years were disrupted, but he was still given a solid foundation for life.

Louisa Bethall’s birth family is shown here; and William and Louisa’s own family is shown here.

Footnotes

1. Exhibit: 1828/513. William Marshall, esq, widower of Leith, Scotland, and formerly of Isle de France [Mauritius]. Probate inventory, or declaration, of the estate of the same, deceased. April 1828. PROB 31/1254/513. The National Archives, Kew. ▲

2. Reduced Annuities and Consols, more correctly called Consolidated Annuities, were government debt instruments that paid a fixed amount of interest each year (3% or 3½%), but which had no set date for the repayment of the initial investment. Investors redeemed their investment by selling their holdings to another investor. [Click the headings in the link to see examples of annuity certificates of the period.] ▲

3. Proctors represented clients in Ecclesiastical and Civil Law courts in the same way as solicitors represent clients today. In English Law and Equity Reports 1853, their duties are defined as: “proctors are officers established to represent in judgement the parties who empower them (by warrant under their hand, called a proxy) to appear for them, to explain their rights and instruct their cause, and to demand judgement.” ▲

4. Letter from Mary Benthall to Helen Davidson (lately governess to the Benthall children) dated 26 September 1821; Hoey private family archive. ▲

5. Asiatic Journal (London, England). Volume 18 July to December 1824. “INDIA SHIPPING.” Pages 94, 96. 19th Century UK Periodicals. ▲

6. Thomas Peregrine Courtenay letter to Thornton Benthall, dated 8 June 1824. Benthall family archive. ▲

7. In the 1861 Census, Elizabeth Milman Varder (aged 86), servant, is shown as living at the Royal Military Asylum, Chelsea, with the late Samuel Adams’s children, Edward (1804-1892) and Mary (1811-1897), neither of whom ever married. ▲

8. Published in History of Devonshire from the Earliest Period to the Present by Rev. Thomas Moore. 1831. Facing Page 73. Original print drawn by T.M. Baynes, engraved by A. McClatchie (Alexander McClatchie), published by Robert Jennings 62 Cheapside, London. 1829. ▲

9. Occasional returns especially of vital statistics, tenants lands to be let and sold, etc., especially from the circular head station, VDL68, Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office, Hobart. ▲

©Megan Stevens 2018